In January 2022, the game Wordle took the internet by storm. Scores featuring boxes of yellow and green were plastered all over social media and became the talk at the water cooler: “how many guesses did it take you to get today’s Wordle?” “What is your starting word…?”

I was swept up in this phenomenon and fascinated by it. Essentially, Wordle is a higher-tech, (slightly) more advanced version of the classic (if morbid!) classroom game, “Hangman.” I was enthralled by the way that, all of the sudden, the conversations that should have been happening in my classroom around words were spontaneously popping up around the lunch table. There was a sudden widespread interest in vocabulary and a community built around words, and I sought to harness that.

The importance and power of this approach is that it was constructed entirely from observing how high school students interacted with Wordle – how they interacted with words and with each other, how they organized large amounts of complex information, and how they sought, found, proposed, and negotiated rules and strategies with more complicated puzzles, and more.

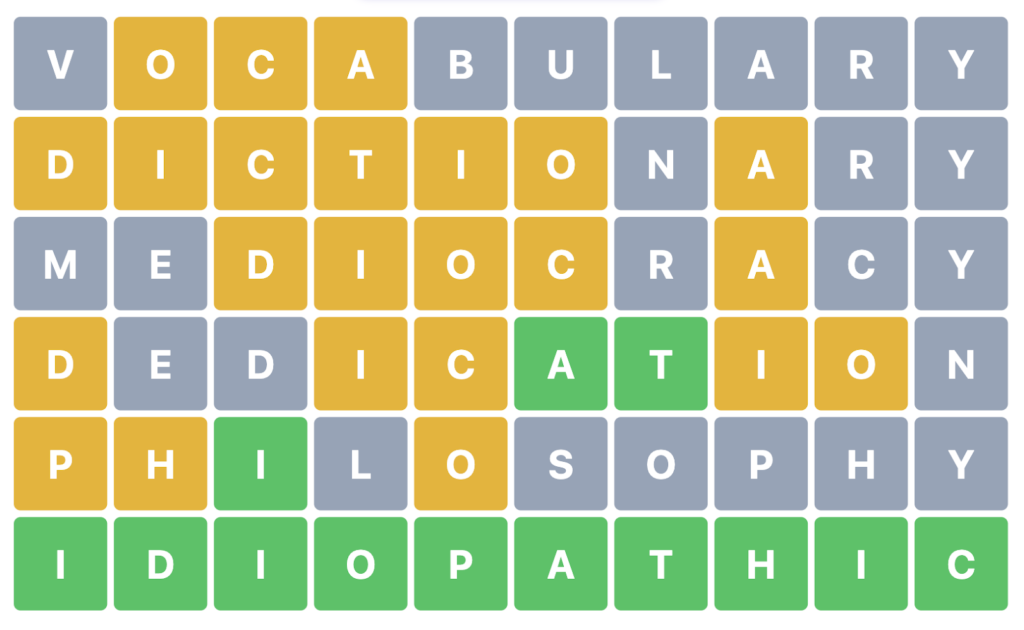

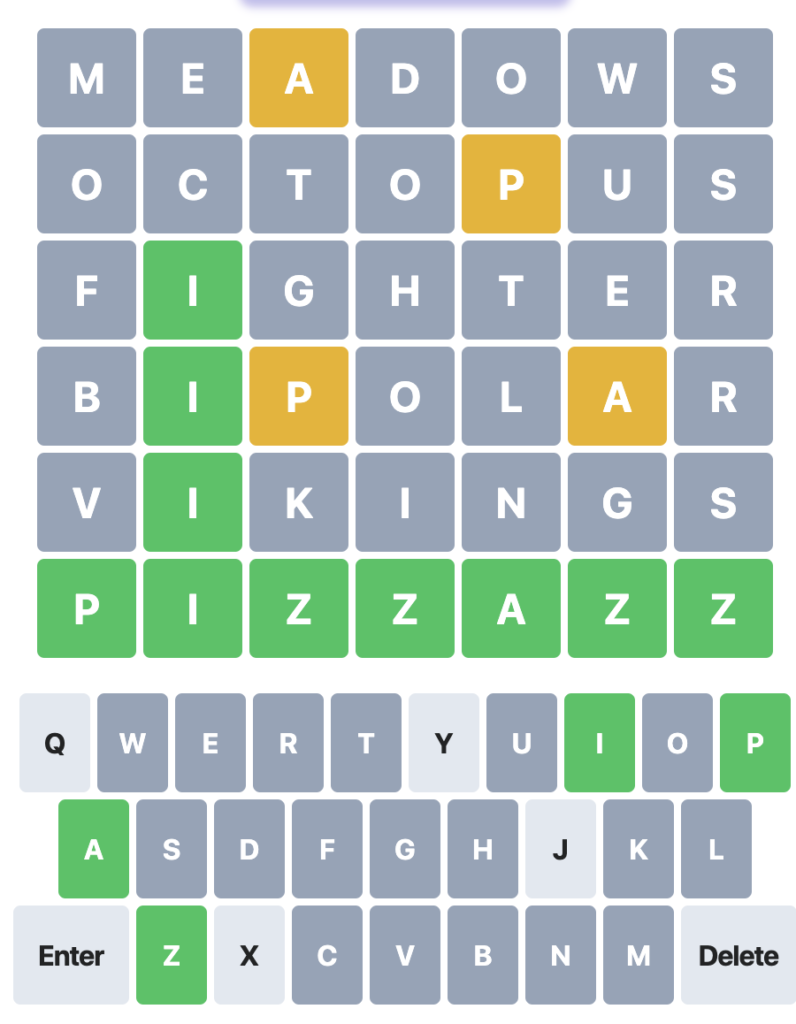

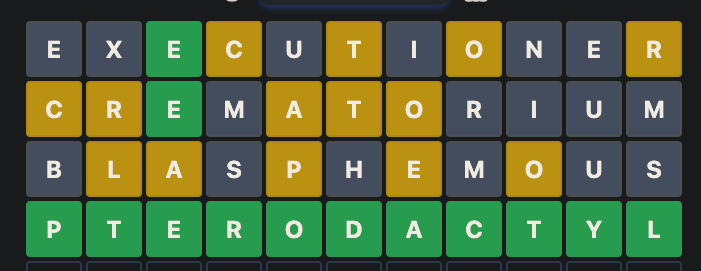

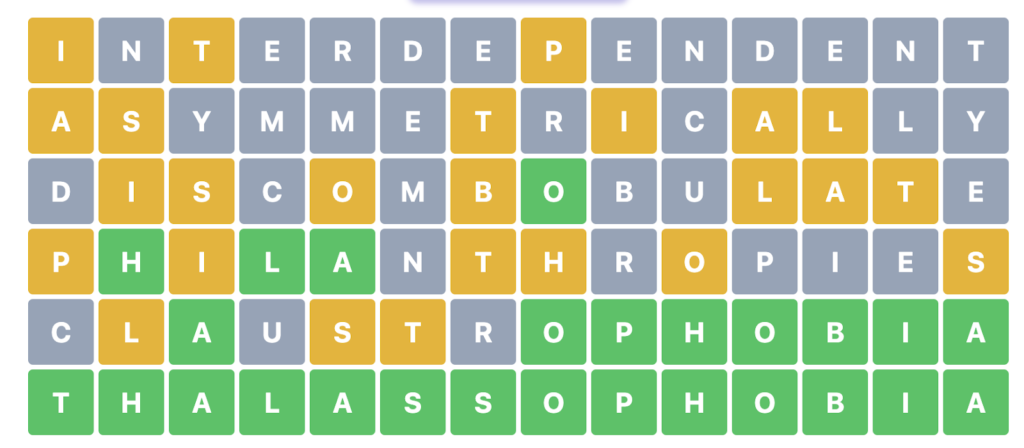

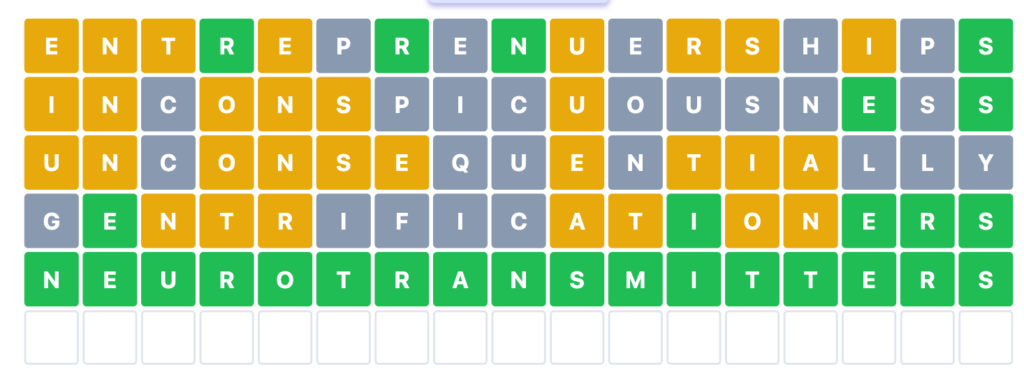

This post will explore the insights gleaned from and explain theoretical rationale for implementing Wordle as formative vocabulary practice. Throughout, you’re going to see screenshots from real puzzles that my students solved this year, and video reflections, observations, and tips that I recorded on this journey, but make sure to follow along for more implementation ideas!

For the sake of framing this discussion, imagine this illustrative scenario:

The first student to class arrives three minutes before the bell. I greet him, and ask, “how many letters should we play today?”

He answers, “Nine.”

I navigate to hellowordl.com on my browser, select nine letters, and airplay my screen to the front of the class.

Another student arrives, and I greet her, and cheerfully ask, “What’s a word about how your day is going?”

She sighs, shakes her head, and answers “tired.”

Another student arrives, so I greet them and ask, “How can we turn tired into a nine-letter word?” and, collaboratively with them or anyone else in the room, we come up with “tiredness.”

The bell rings. Students are settling in. Students begin staring at the board as their minds interpret the yellow, green, and gray letters and their implications. They might begin annotating, sounding out guesses, or constructing word parts, such as “-tion” or “non-.”

A tardy student arrives, and – rather than chide him – I chirp, “Good morning, I am glad to see you! …Give us a nine letter word about why you were late.”

We all have a laugh and he answers, “Bathroom!”

“Bathroom is only 8,” pipes up another student, “Put bathrooms.”

They have six guesses to guess the secret word, and here are their first two guesses:

Can you guess what the secret word was? Try playing the wordle here! (Opens in a new tab)

Vocabulary Instruction through a Social Constructivist Theory of Learning

Constructivist educational theory asserts that learning occurs when the learner constructs meaning when new knowledge and experience combine with prior knowledge and experience, and their new understanding finds space in their mental schema for later use. This theory is especially important for the instruction of vocabulary in the classroom:

Vygotsky emphasized the role of language and culture in cognitive development… language and culture play essential roles both in human intellectual development and in how humans perceive the world. Humans’ linguistic abilities enable them to overcome the natural limitations of their perceptual field by imposing culturally defined sense and meaning on the world. Language and culture are the frameworks through which humans experience, communicate, and understand reality…. As a result, human cognitive structures are, Vygotsky believed, essentially socially constructed. Knowledge is not simply constructed, it is co-constructed. (Berkley.edu)

Collaborative Wordle is powerful formative vocabulary practice aligned to the social constructivist educational theory. Vocabulary is varied, complex, and dynamic, and thus fits into various mental schemas within a learner’s own mind, including but not limited to connotation, denotation, synonyms, antonyms, and parts of speech. However, since the meaning of language is co-constructed in context, most effective learning occurs in community.

The game Wordle asks students to uncover a secret word within six guesses – paradoxically, in order to do this, they must construct the word, not unlike Michelangelo’s famous quote, “I created a vision of David in my mind and simply carved away everything that was not David.”

The truly impressive feat of this vocabulary practice is how much students can use prior knowledge to teach themselves about new words. In order to successfully complete the puzzle, learners must:

- Generate real words for guesses

- Differentiate valid words from invalid ones

- Identify prefixes and suffixes, and their correct usage

- Is it “nonrefundable” or “unrefundable?”

- Compare and contrast word forms

- If we know “stud”, learners connect words like “study,” “student (7 letters),” “students (8),” “studious (8),” “studiously (10),” “studiousness (12),” depending on the length of the puzzle

- Teacher: “This word is 10 letters – how can we make ‘study’ longer? What can we add to the beginning or the end so the word still makes sense?”

- If we know “stud”, learners connect words like “study,” “student (7 letters),” “students (8),” “studious (8),” “studiously (10),” “studiousness (12),” depending on the length of the puzzle

- Correctly employ spelling and grammar rules

- Ex: “Drop the ‘e’ before adding ‘ing’, “i before e, except after c”

- Compare and contrast between words chosen for the other guesses

- “Phrenology” gave us no clues at all but “hitchhiker” gave us several: in what ways are these words different, and what words do I know closer to “hitchhiker”? Should I think about words in a different category than “social sciences,” or should I think about words in the category of “compound words?”

- Spell correctly

Because all of these are required for success, students use which skills they have to acquire the skills they do not. (Ex: if a student knows that the word is 7 letters and thinks it is “skateing,” they can use their knowledge of word forms (noun to verb) to learn that you must drop the “e” before adding “ing” and get “skating.”)

Thus, even if learners do not “know” the word that they uncover, they in fact know a lot about its morphology through their process of discovery, and thus they will feel a natural inclination to fill in the blanks: “I know it’s an adverb because it ends with -ly… with the prefix un-… so it’s an opposite… but how would you use it in a sentence? (definition, usage)” or “It’s a really long word – is this the kind of word only smart or stuck up people would use ? (connotation)”

Importance of the Group

Wordling in community amplifies all of the benefits and adds to them. The power of drawing on prior knowledge and skills multiplies when there are more learners playing along, and this is a uniquely inclusive space as well. Neurodiverse learners – ADHD, autistic, and dyslexic – shine because of their ability to notice and process in creative, out-of-the-box ways. Can we imagine anyone better equipped to make meaning out of scrambled-up letters than a learner with dyslexia? These learners infrequently find opportunities for their strengths in English class, and this is a practice that can bring them in as fully empowered, valuable and valued collaborators.

English Language Learners also bring in cognates from their native languages; recently, an international student solved ULULATE because it was similar to the Italian word for “the sound a wolf makes at the moon.” These students also bring a sophisticated understanding of what English words look like and sound like that native speakers never needed to notice: “It is not going to end with an ‘i’ – English words do not usually end in ‘i,” noted a learner resolutely, for whom English was his fourth language.

“English doesn’t borrow from other languages. English follows other languages down dark alleys, knocks them over and goes through their pockets for loose grammar.”

Terry Prachett

Because Wordling is highly engaging and collaborative, students do not suffer the traditional fear of “getting it wrong” when they propose a guess, support their reasoning, and open it to feedback. It is quickly normalized that throwing out guesses to evaluate if they will offer enough clues is productive: it is hard to tell how helpful a guess could be without group input, and even if the group does not take that guess, it might spark an association in someone else’s mind. This promotes a growth mindset: a posited guess is not “right” or “wrong,” but either a step in the right direction or an instructive thought experiment that can inform what direction to go instead. Risk-taking is encouraged, and critical evaluation of an idea can occur without the same risks to self-esteem as graded or competitive activities.

Thus, the conversation between learners to evaluate the potential benefit of guessing a proposed word is rich with discussion about the word’s relationship to previous guesses, the alignment in terms of word form or spelling, and easily incorporates problem solving and social-emotional skills.

Role of Teachers

During this process, teachers actively listen: what do the students know, what can they figure out on their own, or through collaboration with their peers? In many instances, simply encouraging students through this process is all that is needed. If students are able to draw on prior knowledge successfully individually or together, teachers reinforce this process by modeling the thinking aloud, “Oh, you’re right – we would drop the ‘e’, as in baking or… socializing.”

When students struggle even after this encouragement, the teacher can discuss concepts in more depth, then get students to generate their own examples so they see the knowledge as transferable.

This teaching process is radically responsive to students: teachers teach only what students do not know and cannot figure out on their own or with peers, which begets an empowering environment for learners. They can feel capable and respected in their classrooms, come to see their own strengths and weaknesses more clearly, and prepare to be lifelong learners who trust their own skills and instincts. That said, teachers want students to win, and can skillfully give students the minimum clues they need to be able to solve it themselves: “You have some yellow Ns – maybe think about a prefix like UN- or NON-? What about an ending like -TION or -ING? That could help you find some green letters!”

It is also beneficial for teachers, who can most accurately determine what knowledge and skills students already have, and which they need instruction or practice to acquire. Moreover, when presented as a cooperative game, students immerse in the task and think out loud with their fellow players, adding support to their thinking as they do, thus offering the teacher an authentic assessment of knowledge and skill level that can inform future instruction.

The Importance of Intrinsic Motivation

Children are not empty vessels into which knowledge is dropped. This is a common refrain among educators – and yet it often seems that because the method by which we drop knowledge is the only thing within our actual control, the other part – whether or not our learners receive it – gets lost. Even our well-intentioned instinct to look at “data” to measure our effectiveness puts children into the category of a computer: we have put vocabulary in, what is the “program”’s “output”? But, children are not computers; they are intuitive human beings, with their own experiences, opinions, and cares, and who exist within the parameters of “childhood,” “school,” and “English class.”

“We know now that people are not machines, such that an ‘input’ (listening to a lecture, reading a textbook, filling out a worksheet) will reliably yield an ‘output’. What matters is how people experience what they do, what meaning they ascribe to it, and what their attitudes and goals are. Thus, if students find an academic task stressful or boring, they are far less likely to understand, or even remember, the content.”

Alfie Kohn in Feel-Bad Education 2011, page 4

Vocabulary instruction traditionally includes prescriptive lists of spelling words, required minutes spent in a vocabulary program, or pages read per night, all attached to a grade. This combination of requirement, surveillance, and evaluation causes students to experience what Simon Sinek describes as “a decline of trust, cooperation, and innovation” (The Infinite Game). Alfie Kohn, in his book The Schools Our Children Deserve, summarizes the impact of grades on student motivation: grades cause “diminish[ed] interest in whatever they’re learning, … a preference for the easiest possible task, … reduce[d] quality of thinking” (read more here).

This therefore leaves the teacher in the unenviable position of trying to discern the appropriate level of challenge – which Vygotsky calls the “zone of proximal development” – for students who stand to benefit from obfuscating it. Teachers get stuck analyzing data not for guidance on what their students need to learn, but rather for its validity as a measure of the students in their classroom, especially when that data conflicts with observations. For example, if a student can convince their teacher that they don’t know to “drop the ‘e’ before adding ‘ing,” they can count on the quiz being easy enough for them to ace. The student avoids the risk of a bad grade and the associated negative consequences thereof. This very common situation may be characterized as “lying” or “being manipulative,” or, alternatively, “risk avoidance” or “maintaining a work / life balance,” depending on the perspective of the individual doing the characterization, which is demonstrative of the problem: this dynamic results in an unproductive hierarchical, adversarial, judgmental power struggle that pits teachers against students, when a cooperative relationship is infinitely more conducive to learning.

If indeed children are intuitive, thinking humans, then it is logical that they would perceive the requirement to study vocabulary to mean that they wouldn’t want to do the task simply because it is interesting or valuable – because someone would need to be required to do it. The tracking and surveillance sends the clear message that the task is so unpleasant that compliance must be checked. And evaluation puts an artificial end date on knowledge that is, in fact, ever evolving: have you “mastered” a vocabulary word because you can paraphrase the dictionary’s definition? When you can read it in your book without skipping it or pausing to figure it out? When you can use it in a sentence on demand? When it comes up naturally in conversation? When you can use it ironically, in conversation with another person, trusting that they will “get the joke” because of your shared linguistic and cultural context? Evaluation, in a traditional grading sense, assigns an artificial end date, and the criteria for passing the evaluation are often quite disconnected from the natural process of an expanding vocabulary.

To meaningfully differentiate between “delivering instruction” and actual “student learning,” the disposition of the learners matters. Are they interested, are they curious, are they invested, are they having fun? These terms might strike adults as frivolous, but they are in fact simply developmentally appropriate ways to communicate with learners about their zone of proximal development: children will dismiss what is too easy as “boring,” what is too difficult as “overwhelming” and what is just above their level of skill as “fun” and “interesting.”

Learner disposition matters even more so if the goal of education extends beyond what happens in the classroom into establishing a desire for lifelong learning.

For lasting learning to occur, the environment must break down these barriers and allow room for authentic interest and engagement. Wordle is rich in everything intrinsically motivating about learning vocabulary – because “learners are partially motivated by rewards provided by the knowledge community… learning also depends to a significant extent on the learner’s internal drive to understand and promote the learning process” – if, and only if, educators can resist the urge to require, quantify, or grade it.

“Infinite games have no finish line and the goal is to keep the game going as long as possible… We have to recognize what type of game we’re playing and then play with the right mindset of the game we are in.”

Simon Sinek, The Infinite Game

“Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.”

Albert Einstein

Compliance kills curiosity, grades kill exploration, and hierarchy ignores or distorts the assets that everyone brings to the game: students bring the exceptional ability to be cognitively creative, intuitive, and flexible, and teachers bring experience and expertise.

The goal between these roles is the same: win the game, and get better at winning the game.